The Candy Man and Elijah Girl

Hitler is dead, but his ideology of hate is not. Because we have been given the gift of survival - and life is truly a gift - we must fight that darkness and its enablers with all our might.

This Substack posting is an abridged and updated version of a Holocaust-based sermon given on Yom Kippur, 2017. You can listen to the complete sermon by clicking below, and you can download it to your device by clicking here.

Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day on the Jewish calendar, begins at sunset today.

In mid-2017 one of the most remarkable news stories I’ve ever seen came across the wires. The oldest person in the world – Guinness-certified as the oldest for over a year - died at the ripe old age of 113. His name was Yisrael Kristal, and Yisrael lived in Israel. A nice touch, but that’s not what’s most remarkable.

He celebrated his “bar mitzvah plus-100” when he turned 113, which is also not the most remarkable thing, though it would have been if his voice had cracked and in his speech, he’d made a joke about his annoying little brother.

In fact, this second bar mitzvah was really his first, because when he turned 13 a hundred years before, his mother had just died and his father was fighting in the Russian army during World War 1. Amazing, but not the most remarkable thing about Yisrael.

Oh, and he was observant and prayed every morning after his 13th birthday. Amazing. But not the most amazing thing.

Oh, and he had a sweet tooth and made a living running a candy factory in Haifa. And in his younger years, he owned a candy factory in Lodz – he was the candy man of the Lodz ghetto. Remarkable. His children were killed there – but he lived on.

Here’s what’s most amazing. The world’s oldest man was a survivor of Auschwitz. And when he was liberated, he weighed all of 81 pounds. His wife died there, but he survived, moved to Israel and began a new life. Like a modern-day Job, he started anew and died “old and full of days,” and felt so blessed that he never stopped praying, which, come to think of it, might be just as remarkable as his having survived Auschwitz.

In Deuteronomy 30, the Torah presents us with a stark choice:

See, I set before you today life and prosperity, death and destruction…. life and death, blessings and curses. Now choose life, so that you and your children may live…. For the Lord is your life…” כִּי הוּא חַיֶּיךָ

God is life....

Everything had been laid out for Yisrael Kristal – the good and the bad; he was born three months before the Wright Brothers first flight, so he had seen remarkable progress. But he had also seen the world’s darkest hours – and yet, and yet, he chose life.

He was lucky to live – very lucky, surviving not only Auschwitz, but wars, pogroms and the Lodz ghetto, not to mention all that Israel, the state, has endured for the past 80 years.

But he could easily have chosen to die. Yisrael chose life. And not just life – but life in a candy factory, life with a cherry on top.

After the Holocaust, many can no longer believe in the same God that our great-grandparents believed in. Elie Wiesel in his book “Night” echoes the notion shared by many that God of Sinai died at Auschwitz. But perhaps a different understanding of God was born there. Perhaps God, the life force and our survival instinct are somehow intertwined.

What was the secret of his survival? Maybe it was his chosen profession. For Yisrael, life literally was a box of chocolates. And his grandson noted that when Yisrael was 12, during World War One, he was also a booze smuggler. “He used to run barefoot in the snow” for miles every night, smuggling alcohol between the lines of the war.” What a guy! Even when he wasn’t Guinness’s oldest, clearly, he was still the most interesting man in the world.

Is it conceivable that the living hell that was Auschwitz propelled this man to cherish life so much that he became the oldest living human? Could a man who was larger than life have been propelled to fame by a place that was darker than death?

For much of my career, I’ve called upon Jews to stop running away from the Shoah – because we can’t. It is in us. It is part of the fiber of who we are. And it is a key component of what we need to teach the world, an incredibly potent and resonant event for Jews and non-Jews alike. That’s where my book, Embracing Auschwitz: Forging a Vibrant, Life-Affirming Judaism that Takes the Holocaust Seriously came from.

Seventy-six percent of American Jews believe that remembering the Holocaust is a key to being Jewish, and nothing else even comes close. That number, from 2021, went up from seventy-three percent in the prior Pew survey in 2013. We need to embrace it, to embrace all of it, and as we do, to forge a new Jewish vision for ourselves and for the world.

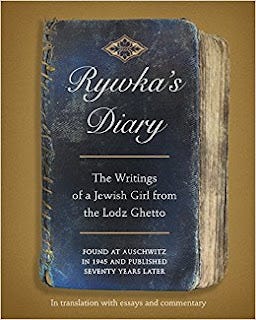

The Holocaust is filled with remarkable stories of survival, even among those whose survival may have been temporary. There was Rywka Lipszyc, a 14-year-old Jewish girl, orphaned and living in the Lodz ghetto. From October 1943 to April 1944, she recorded her thoughts, feelings, hopes and dreams in her diary. Along with 67,000 other inhabitants of the Lodz ghetto, Rywka was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau in August 1944. Nearly a year later, in June 1945, her diary was found in the ashes of the crematoria by a Soviet army doctor (read more about Rywka and her diary here).

Like Anne Frank, Rywka was a simple teenager living a simple teenage life. But Anne Frank wrote from the relative safety of her secret annex in Amsterdam – and although that security was fleeting, it could not compare to the hell that was the Lodz ghetto (read about other children's diaries to have survived the Holocaust).

The diary of 112 pages was written between October 1943 and April 1944. It details Rywka’s activities at work and in school, her relationships with her friends and family and events in the ghetto. Despite the devastating conditions she endured, Rywka “worked, studied, participated in literary clubs and cultural activities, wrote poetry, and dreamed of a better future."

Here’s an entry from Feb. 1944, as she grieved the death of her mother.

“…Once upon a time, when I was five, maybe six…or maybe younger…it was evening and Mommy was sitting around the table and I….I was saying stupid, childish things that hurt Mommie a lot. …Oh even today I’m full of remorse for those words, although I was a child who knew almost nothing….” I know what I had and what I lost. Oh, will I ever be a mother?”

Much of the diary dwells on everyday activities – what I call the “nobility of normalcy.” But there are times when her ability to find light in the darkest of nights is absolutely stunning.

In one entry, she talks about a book she is currently reading, Victor Hugo’s “Les Misérables.” I’m sitting there wondering whether this was escapism for her. Did she imagine herself as young Cosette, another orphan, waiting for her Jean Valjean to come and rescue her?

The next day, March 5, she thinks of her mother and begins to well up. “I can’t write because of my tears,” she exclaims. “Oh, I’m suffocating. I’m choking. My dear God, what will happen to me?” Then she immediately collects herself. “Enough. It’s always the same. I have to do an examination of conscience…to persevere.”

In entry after entry, this remarkable resolve, this true grit, is played out, in the frail body of this fourteen-year-old. March 7: “I’ve fallen…or rather I’m falling. I have to lift myself up. It's important.”

On April 11, 1944, she writes:

“Thank you, God, for the spring! Thank you for this mood! I don’t want to write about it, because I don’t want to mess it up, but I’ll write one very significant word: hope!”

That passage is exactly 140 characters long - Maybe the most inspirational Tweet ever.

This was at a time when she was still deeply grieving the loss of both her parents. But warm weather lifted her spirits.

Here's her final entry, written the very next day:

At moments like this I want to live so much. There is less sadness, but we’re more aware of our miserable circumstances, our souls are sad and…really one needs a lot of strength not to give up. We look at this wonderful world, this beautiful spring, and at the same time we see ourselves in the ghetto being deprived of everything…. How hard it is! Oh God, how much longer? I think that only when we are liberated will we enjoy a real spring. Oh, I miss this dear spring.

That’s where it ends.

We know that Rywka survived Lodz and that she also survived Auschwitz. Then she survived the death march to Bergen-Belsen and she even lived to see the liberation. She was too ill to be evacuated, however, and the record of her life ends.

Her final whereabouts remains a mystery, which perhaps is as it should be. Her name last pops up in records of a hospital in Germany.

So who knows? Like the immortal Prophet Elijah, Rywka may still be among us, hopping from Seder to Seder, looking for her mother. Her diary’s recovery was itself miraculous – her survival would be all the more so.

The survival instinct fills all that live. Studies show that the sweetness of a carrot is generated by its struggle to survive in cold weather. Maybe that same proclivity for sweetness was the key to candy man Yisrael Kristal’s longevity.

“Kol Haneshama Tehalel Yah!” “All who have breath praise God,” says Psalm 150.

And perhaps our praise of God is manifested simply by breathing, simply by staying alive. No need for a prayer book. Just breathe. That “Choose life” verse in Deuteronomy adds, “Ki Hu Hayyecha.” For God IS your life. Literally, God IS life. God is breath. Breathing IS praying. If you take any prayer or story and substitute the term “Life Force” for “God,” you end up with a much more palatable post-Holocaust theology.

After the Holocaust, many can no longer believe in the same God that our great-grandparents believed in. Elie Wiesel in his book “Night” echoes the notion shared by many that the God of Sinai died at Auschwitz. But perhaps a different understanding of God was born there. Perhaps God, the life force and our survival instinct are somehow intertwined. If God is the sheer will to live, then Yisrael Kristal and Rywka Lipszyc are His prophets.

Post-Holocaust theology is too complicated a topic for me to address fully here, but in this new era, the survival of Yisrael – not the individual, but Yisrael, the collective, the Jewish people, is a commandment that stands on its own, with or without God. The philosopher Emil Fackenheim called it the 614th commandment: not to give Hitler a posthumous triumph by abandoning Judaism. (see more on Fackenheim, Yitz Greenberg and Holocaust theology here).

By this logic, when we proclaim “Am Yisrael Chai,” (The People of Israel Lives) is no longer merely a fun song to dance to at bar mitzvahs or a rallying call after October 71 – it has become an imperative – a life’s mission, to keep the Jewish people alive. It certainly has been mine - which is why I care so much about Israel, enough to call it out when it goes astray, as so often happens with the current government.2

With all the 80th anniversaries to be commemorated this year, one that all of us should pay attention to is the anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, on Aug. 6. A website has been set up for the commemoration, and I’ve started rereading John Hersey’s classic work, Hiroshima, which originally was an article in the New Yorker. In journalism school, my teachers cited it as the greatest work of journalism ever. Just the first paragraph is - pardon the expression - searing.3

In Hiroshima, the ginkgo trees are called survivor trees – and how did they manage to overcome the fallout of a nuclear blast? It’s because they have very deep roots. Our roots are unnaturally deep as well. Any other people would have given up after the Shoah.

These Jews have chosen life. They have chosen to see “Am Yisrael Chai” not as a song, but as a summons. That is the call following Auschwitz – Choose life, collectively, because survival IS victory.

Hitler is dead and we have survived, but his ideology of racism and hate is not. And because we have been given the gift of survival, we Jews shall fight that darkness and its enablers with all our heart, all our soul and all our might.

Who shall live and who shall die? Well, we all shall die. It’s like the Buddhist coroner who lost his job because, when she was filling out the forms, whenever she came to “cause of death,” she would write, “birth.”

For the Jewish coroner, the cause of death would better be put as “heroic struggle against impossible odds.”

We are all individually mortal, but the Jewish people? We are immortal – like the ginkgo tree – but only if we do our part.

It is now a commandment for the Jewish people to live, not to spite Hitler, but to teach the world what Hitler did – and to guarantee it doesn’t happen again. It is essential to the future of the world that we survive – in order to tell our story.

Choose life, so that you – and all of humanity – may live.

It is said that every Jew, past present and future, stood at Sinai. Well, every Jew stood in those gas chambers too, and it didn’t matter whether you were male or female, traditional, liberal or secular, born Jewish, converted to Judaism or married to a Jew. By embracing the memory of Auschwitz, we can come together, Jews of the broadest possible definition, to proclaim to the world that Auschwitz must never happen again.

So we must constantly recall that “Am Yisrael Chai” is neither a statement nor a song – it is, for us, a commandment.

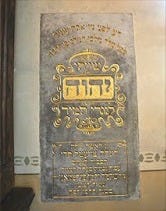

At the Galicia Museum in Krakow, there is a photo of a stone tablet, similar to tablets that were quite common in synagogues throughout Poland before the war. It says, in Hebrew, the verse from Psalm 16 that many synagogues have over their arks, “Shiviti Adonai l’negdi tamid,” “I have set God before me always.”

What makes this find so important is that this is the only such pre-war tablet to have survived intact in Polish Galicia (p.26, Galicia Jewish Museum book)

What makes it so astonishing is that this simple, pure statement of faith and continuity, the only one to have survived intact, the ginkgo tree and Yisrael Kristol of unbroken decorative stone tablets, a stone tablet that not even the Nazis could destroy – or Moses, for that matter, who shattered the tablets of Sinai at the slightest provocation – this tablet was found at the last remaining synagogue in the pretty, tree-lined Polish countryside town of Oswiecim.

You might know its German name: Auschwitz.

Just one mile from the hell that nearly destroyed the Jewish people and all of human civilization, within walking distance of the ovens, somehow this reminder of a bygone, simpler era withstood the fallout of the moral nuclear detonation that took place right down the street.

We are all survivors. And maybe God is a survivor too. But after Auschwitz, maybe the God of Psalm 16, the one that we place before us, the ultimate goal that we aim for, IS survival itself, is that life force, the instinct that drives us to breathe and to love and to find hope among the ashes – as exemplified by an innocent, precious girl’s diary found next to the crematorium – the frail girl who lost both parents in Lodz and had little chance of living, but who allowed a gorgeous spring day to intrude on her gloom. Our talent for survival is embodied in that fragile fourteen-year-old who survived Lodz AND Auschwitz AND the death march AND Bergen Belsen – and, in our dreams, at least, this young Cosette may still be alive today.

She IS our new Elijah. She is the one to visit every Seder, even if she is still underage for the wine. She is the one to make us care about lonely and the forgotten, while she searches for her mother, to bind ourselves to our neighbor in one human tapestry. And she is the one to envision new possibilities emerging out from the very ashes where her diary was found.

Rywka wrote these wise words in her diary, words that I believe will someday become part of our liturgy - every bit as inspirational as Anne Frank's assertion ,"In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart." Rywka wrote:

I am just a tiny spot, even under a microscope I would be very hard to see – but I can laugh at the whole world because I am a Jew. I am poor and in the ghetto, I do not know what will happen to me tomorrow, and yet I can laugh at the whole world because I have something very strong supporting me – my faith.

Whether or not she is still alive, Rywka has had the last laugh on her tormentors.

Whether or not she is still alive, she is directing our gaze, with hope, to the future.

Which is exactly what the Holocaust is at long last able to do.

We place life before us always – ever mindful of the gift that is life and the responsibility that survival implies. All the more, for the survival of the Jewish people.

Survival is victory. But only if we earn it, by translating it into a life of service. And if we do, Yisrael Kristal, that 113-year-old modern Methuselah would tell us, that life, in the end, is like a box of chocolates. The Candy Man and Elijah Girl have taught us to thoroughly enjoy every bite, anticipating with mouthwatering expectancy whatever will come next.

Because, you never know what you’re gonna get.

But survival sure is sweet.

This new version of the song by Eyal Golan has become an anthem of resilience in Israel post- Oct, 7

See the full text, not paywalled, of Shin Bet head Ronen Bar’s damning eight-page affidavit, submitted to the High Court of Justice on April, 22 2025, regarding the petitions against his dismissal. This Times of Israel translation retains the original document’s format and wording.

See also: Today’s commentary on the matter from Ha’aretz, by Dahlia Scheindlin:

Coup, Crimes and Conspiracy: Israel's Spy Chief's Most Shocking Accusations Against Netanyahu

Ronen Bar's shocking affidavit to the High Court of Justice, highlighting Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's alleged demands for complete loyalty to him, reveal everything that's wrong with Israeli governance

That classic first paragraph of Hiroshima:

At exactly fifteen minutes past eight in the morning, on August 6, 1945, Japanese time, at the moment when the atomic bomb flashed above Hiroshima, Miss Toshiko Sasaki, a clerk in the personnel department of the East Asia Tin Works, had just sat down at her place in the plant office and was turning her head to speak to the girl at the next desk. At that same moment, Dr. Masakazu Fujii was settling down cross-legged to read the Osaka Asahi on the porch of his private hospital, overhanging one of the seven deltaic rivers which divide Hiroshima; Mrs. Hatsuyo Nakamura, a tailor’s widow, stood by the window of her kitchen, watching a neighbor tearing down his house because it lay in the path of an air-raid-defense fire lane; Father Wilhelm Kleinsorge, a German priest of the Society of Jesus, reclined in his underwear on a cot on the top floor of his order’s three-story mission house, reading a Jesuit magazine, Stimmen der Zeit; Dr. Terufumi Sasaki, a young member of the surgical staff of the city’s large, modern Red Cross Hospital, walked along one of the hospital corridors with a blood specimen for a Wassermann test in his hand; and the Reverend Mr. Kiyoshi Tanimoto, pastor of the Hiroshima Methodist Church, paused at the door of a rich man’s house in Koi, the city’s western suburb, and prepared to unload a handcart full of things he had evacuated from town in fear of the massive B-29 raid which everyone expected Hiroshima to suffer. A hundred thousand people were killed by the atomic bomb, and these six were among the survivors. They still wonder why they lived when so many others died, Each of them counts many small items of chance or volition—a step taken in time, a decision to go in-doors, catching one streetcar instead of the next— that spared him. And now each knows that in the act of survival he lived a dozen lives and saw more death than he ever thought he would see. At the time, none of them knew anything.

Thank you, Rabbi. This was moving and important for me to read. ¡Saludos!

Hitler isn’t dead, he’s alive and well and living in Israel and his name is Netanyahu