New Year's Resolutions, Jewish Style

At a time when so many are leaving religion, we need to be reminded about what is beautiful and good about our traditions. In Judaism, it's all about mitzvah - where practice makes purpose.

On the surface, there would seem to be very little that the Jewish New Year and the secular one have in common. But there is one thing that the two celebrations share, and that is the idea of New Year’s resolutions. Jews call it “teshuvah,” which many translate as “repentance,” but actually means a return to the rock-solid values of a simpler life. Secular New Year’s resolutions can be much the same.

So how do Jews choose their resolutions? Whether by looking at the bathroom scale1 or the scales of justice, for us it always comes back to one untranslatable term: mitzvah.

At a time when so many people of faith are deconstructing2 and leaving religion behind, we all need to be reminded about what is beautiful and good about our diverse religious traditions. And a time when antisemitism is rampant, Jews need especially to be reminded about what is beautiful and good about Jewish traditions. This weekend might be time for all of us, Jews and non-Jews, to begin reflecting on acts of religious affirmation that we can feature in 2025. We Jews call those signature acts of holiness mitzvahs, or, in the Hebrew plural, mitzvot.

What is a mitzvah?

The most common translation is “commandment” or “law,” and the root letters "צ-ו-ה" (tz-v-h) come from the verb “to command.” But a mitzvah is so much more than, say, commanding your dog to sit or ChatGPT to write this essay (I didn’t). For one thing, while Jews are historically bound by covenant to perform mitzvot, there is also a great degree of choice on whether and how to embark on that journey.

Mitzvot are opportunities to open ourselves up to a life of greater meaning and purpose, to make the most of our God-given talents. But not in isolation. For the path of mitzvah is the path of bonding.

Some derive the word mitzvah from the expression “tzavta,” which is the Aramaic word for “connection” or “joining.” Through simple acts, we bond together what is divine with what is human and we connect ourselves to people everywhere.

Mitzvot are the mountain peaks where heaven and earth meet, where the mundane becomes sacred, where the religiously numb become spiritually sensitized.

In this green era, the mitzvah is also a cheap source of renewable spiritual energy. And how do we energize? By taking on more. By stockpiling our mitzvot. As the Talmud states (Avot 4:2), "One mitzvah leads to another mitzvah."

But each of us must also specialize.

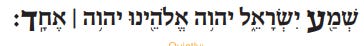

The Rabbi Mordechai Leiner, also known as the Ishbitzer Rebbe looked at the Sh’ma3 - Judaism’s central prayer - and asked what does it mean to “Love the Lord your God with all you heart, with all your soul and with all your might?”

“Everyone has a particular mitzvah,” he proclaimed. “By fulfilling it, that person achieves the world to come – this mitzvah and its fulfillment become the essence of that person’s whole existence.”

So, whether you are Jewish or Gentile, deconstructing or reconfirming, let me suggest that you designate a personal signature mitzvah as your New Year’s resolution for 2025.

And given that the purpose of this Substack is not to proselytize but to help people along their own paths, I should emphasize that there are parallels to mitzvot in other faith traditions (though with key differences) such as Good Works in Christianity, Islam’s Five Pillars and Dharma in Hinduism,4 Buddhism5 and the Jain philosophy.

Back in 2009, the world was reeling from the financial meltdown, and for the Jewish community especially, the Madoff scandal took an enormous financial and emotional toll. Knowing that from crisis emerges opportunity, on the High Holidays that year I proposed a re-set, and a chance to reimagine the meaning and role of mitzvah in our lives. I saw mitzvot as a grand spiritual stimulus package Jews could offer the world.

You can read the text of the sermon here. Audio is below.

The same is true today. At a time of deep uncertainly, we need to grab hold of ways to make the world better, one mitzvah at a time.

A Mundane Act With Cosmic Resonance

A mitzvah is a very human act, but one that reverberates throughout the cosmos. While mitzvot are ordained from on high, many Jews perform them for reasons that are most mundane.

Some light candles because their parents did.

Some go to services because they get to schmooze with their best friends.

Some send clothes to Goodwill because their closet is so stuffed that the door won’t close.

So what’s your mitzvah?

A signature mitzvah can become the key to our immortality. The Talmud states, “The righteous require no monuments - their words are their memorials.” Words - and deeds.

There is a midrash that when a person is asked in the world to come, “What was your work?” and they answer, “I fed the hungry,” that person will be told, “This is the gate of the Lord, enter into it, you who have fed the hungry.” The same goes for those who reply that they raised orphans, performed acts of tzedakkah, clothed the naked and embraced acts of lovingkindness (Midrash Psalms 118:17).

So what will you say when you reach paradise? What will your descendants be saying about you?

613 Mitzvot

Think about it: There are, according to Maimonides’ count, 613 mitzvot in the Torah. Some of them are no longer in play and others are only meant to be observed in Israel – but we should check out that list and pick one. Or better yet, more than one. We do many mitzvot, after all, and often without knowing it.

So what will your signature mitzvah be?

To attend services more often? To make your community greener? To tutor? Or run a support group for those who struggle with addiction. For Maimonides, there is no mitzvah greater than the redemption of captives - so more advocacy on behalf of freeing the October 7 hostages would be an excellent choice.

There are a number of mitzvah heroes that I’ve known over the years. One helps with job networking, and another with food drives. Another visits people in the hospital in a clown costume. One student of mine taught Hebrew songs to a bunch of schoolchildren in India and another served up vitamins to Ethiopian immigrants in Netanya.

As a rabbi, I consider myself somewhat of a general practitioner, but I’ve also got more than a few signature mitzvot.

One that I embrace is the one listed as #16 on Maimonides’ list of 613; it is a mitzvah for everyone to write a Torah for himself. I see my own writing in that light, as an attempt to bring the Torah to life through the prism of my own experiences. I also like #28, not to harm anyone in speech, though it’s hard and I often fall short. And there’s #39, to unburden animals, and the 150s, which all deal with aspects of keeping Kosher. And then there’s the 170s, which all deal with business ethics. I care about those.

And one more signature mitzvah: #53. Love the stranger. The Torah repeatedly commands us to love the stranger, because we were strangers in Egypt.

If you return a lost item, you’re doing a mitzvah – # 276. So if someone lent you something years ago and you just came across it, but you weren’t really sure what to do – return it! If you have one of my books, for instance, I’m declaring an amnesty period for the next month. No questions asked.

If you care for an animal, you’re doing a mitzvah. So adopt a dog and name it mitzvah. Throw a yarmulke on it and have a bark mitzvah….

If you’ve been carrying a grudge, end it. #32. If you’ve been gossiping, stop it. #28. If you are known for angry outbursts (and who isn’t these days!), cool it – #30. If you’ve given tzedakkah6, give more – #52. If you’ve never performed a bris… …maybe hold off on that one… but it’s #17.

Many of the 613 mitzvot are obscure, some have become obsolete, and others are downright objectionable. But the act of struggling with mitzvah in itself connects us to our roots and to one another. Maimonides wasn’t the last word on Torah, which is fortunately a living document. The mitzvah map is changing all the time. There are plenty to choose from, though. So find one that means something to you.

Then just do it. For the New Year.

Practice Makes Purpose

I know of one rabbi who asked his entire adult ed class to go home and light candles that Friday night. The response was amazing.

One student came back and said “My family laughed at me.”

Another said he went upstairs and lit them in the closet. (I don’t recommend that).

And a third told the teacher, “I went home and lit candles last Friday night – and my husband cried.”

You know, it’s interesting that we always use the expression that we practice mitzvot. We’re always practicing. We never get it right!

In Judaism, practice never makes perfect. But practice, in both senses of the term, makes something much more important.

Practice makes purpose.

Practice makes holiness. Practice brings hope. Practice brings bonding. Practice brings people together. Practice brings communities together.

Practice brings heaven and earth together.

But don’t do it for any reward7 - or “mitzvah points,” as we used to call them. Think of Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, who said, “Expecting the world to treat you fairly because you are a good person is like expecting the bull not to charge at you because you are a vegetarian.” 8

Kaplan had a decidedly secular term for mitzvot. He called them folkways, but they were no less important to him, even without the notion of a personal God meting out reward and punishment. Whatever your beliefs about God, Kaplan understood that without ritual practice, there is no Jewish civilization. And as the founder of Reconstructionist Judaism, he demonstrated that commandments can exist quite well without relying on a personal deity.

It’s ironic to quote the founding Reconstructionist, since right now so many who grew up in faith-filled homes are finding themselves“deconstructing” and leaving their childhood traditions behind altogether.

For so many people, at a time where so much in our world needs to be reconstructed, what better way to begin than with a simple act of affirmation that the building blocks of faith are acts, simple, mundane acts. Sociologist Arnold Eisen says that the question of mitzvah is not about theology, it is about our desire to be different, to stand out, to make the case that change is possible and to declare it to the world.

So if you are looking for a path to a more purpose-filled life, choosing a signature mitzvah as your New Year’s resolution and adapting it to your particular theological bent or faith tradition, can be a very good start.

Happy 2025, and I thank you for your support of this Substack community. My best wishes to all of you for year of good health and deep purpose. We have so much work ahead of us.

The Mitzvah of Health (Jewish Journal) - Our tradition calls the mitzvah of health shmirat haguf — literally, “guarding the body.” In the book of Deuteronomy, we find the verse, “Guard yourself and guard your soul very carefully” (Deut. 4:9). Biblical commentators have understood this to be the religious imperative of taking care of both body and soul. As the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria put it, “The body is the soul’s house. Therefore, shouldn’t we take care of our house so that it doesn’t fall into ruin?”

On deconstructing, see this recent story from RNS: New book explores research on how to flourish after being 'done' with religion. Also see TikTok’s Rev. Karla says Christian women stuck in patriarchy find solace online

Here’s my in-depth commentary on the Sh’ma, translating it into 20 languages, and looking at it from a number of perspectives.

From the Sanskrit root dhri (which means “to support,” “to hold,” or “to maintain”), dharma is described in early Vedic texts as laws that bring order to a universe that would otherwise be in chaos. Sacred texts and stories further espouse dharma as actions most conducive to maintaining family and society, both of which would also otherwise fall into chaos. It should therefore come as no surprise that the attempted one-word English translations of dharma provided by scholars are numerous, including words like “law,” “duty,” “custom,” and “model,” all of which ultimately serve in preserving or holding together the structure of an organized system.

In Buddhism, dharma is the doctrine, the universal truth common to all individuals at all times, proclaimed by the Buddha. Dharma, the Buddha, and the sangha (community of believers) make up the Triratna, “Three Jewels,” to which Buddhists go for refuge. In Buddhist metaphysics the term in the plural (dharmas) is used to describe the interrelated elements that make up the empirical world.

What is Tzedakkah? Tzedakkah is not charity, Charity is from the Latin caritas which means to care. It is important that we care, but that is the realm of G’milut hasadim, those acts discussed last week. The goal of tzedakkah is tzedek, justice, to leave the world more perfect than we found it -- to make things right. Some call it Tikkun Olam, world repair, and that analogy aptly it turns us from benefactors to handymen and women. When we practice Tikkun Olam in this spirit, we no longer ask, "Why is there suffering?" but rather "What can I do to alleviate suffering?" We no longer ask, "Why did that SOB toss garbage on the sidewalk?" but rather, "Where is the nearest trash bin so I can properly dispose of the garbage that idiot tossed on the sidewalk?" The person imbued with this spirit doesn't deny him or herself basic financial needs and even some luxuries, but once those are taken care of, the focus is decidedly out there.

Tzedakkah heroes are people with the tool belts on, who see a need and fix it. They can be wealthy, like the Bronfmans, Wexners, and Steinhardts, who have seen a crying need for bold initiatives in Jewish education in this country and are taking it on big-time. And then there’s Kimberly Cook, the inventor of the Braille beeper. Nine years old at the time, not blind, neither are her parents -- she just put 2 and 2 together: beepers and blind people, consulted other tinkerers and experts and came up with a beeper with braille numbers. She is a tzedakkah hero too. The sage Hillel once said to a group of his students, "If a man has 1,000 dinars and gives 300 to the poor, how much then does he have?""Seven hundred," the students replied. "Not so," declared Hillel. "He truly possesses only the 300 dinars he gave to tzedakah. He may lose the other 700 by accident, or in a business venture, or with luck, he may leave it to his children. Therefore, know that all a person truly possesses for eternity is the money that person gives away." See more in this sermon from Yom Kippur, 1998

Here’s a good overview of Jewish perspectives on reward and punishment.

More on reward and punishment: Numbers 15:40 teaches that we should wear the tzitzit (fringes at the corners of the prayer shawl) “Le’m’a’an tizzzkeru,” “so that we will be reminded.” In other words, so that we will remember that God rescued us from Egypt and then gave us these commandments. It is traditional when praying this passage to stretch out the “z” sound in tizzzkeru, because if we mistakenly pronounce it “tisskeru,” with an “s” instead of a “z,” then it would mean “you shall be rewarded,” which implies that the only reason to follow the commandments would be to get a reward (Rabbeinu Bahya, Bamidbar 15:40:1) That’s something we should try to avoid.

Ver well said, Rabbi Joshua. True wisdom. HNY!! https://thegoldenmean2040.substack.com/p/respect-whose-opinions-matter

Loved this.

Mægen is defined as strength, power, vigor, valor, virtue, efficacy, a good deed, a miraculous event (and the power behind it). Modern Heathens often use this term in reference to spiritual and moral power.