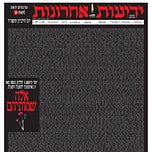

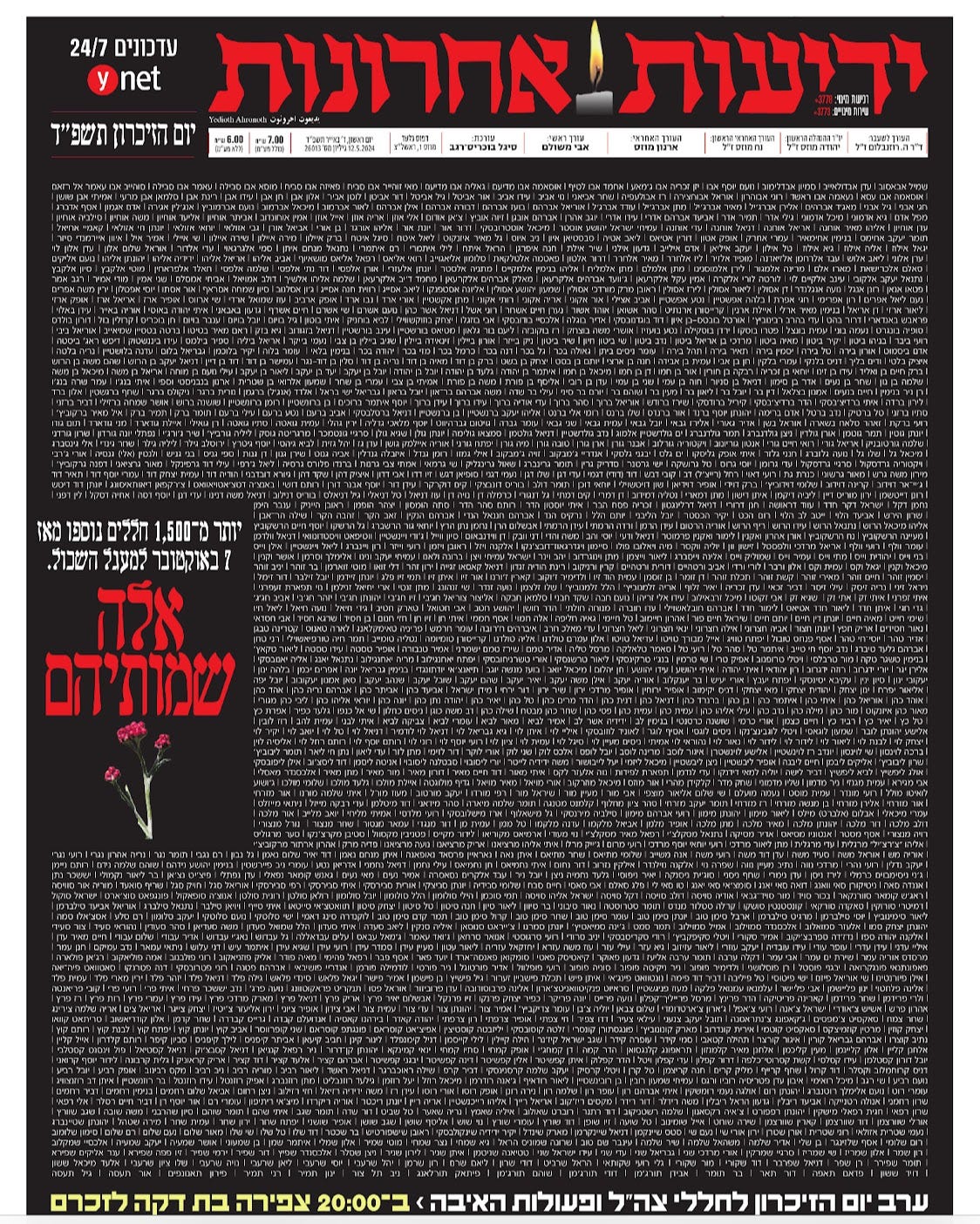

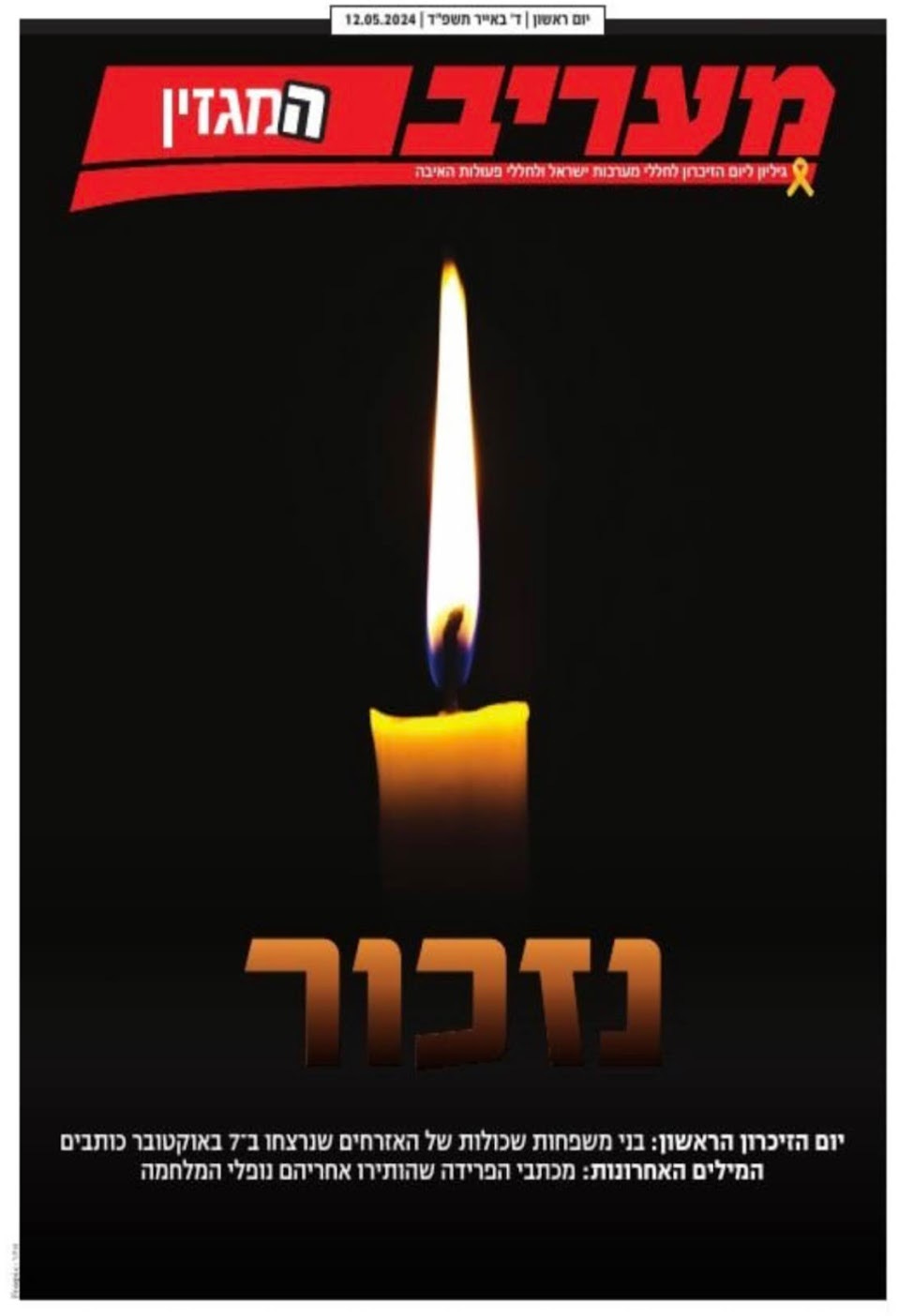

As Israel enters its most excruciating Memorial Day yet, the newspapers are covered with the names of those who have died just this past year in terror and in war. Above, on the front page of today’s Yediot Achronot, are all the names added this year to the nation’s “circle of bereavement.” (Click to see a clearer, full-page pdf with all the names.) Yet all those names, when added together, equal one. One solitary memorial candle, as burns on the front page of Ma’ariv’s special memorial section.

Hundreds and hundreds, thousands upon thousands…the Israeli government’s official count, as of today, is 25,034 men, women and children who have been killed in terrorist attacks and in defense of the Land of Israel since 1860, the year that the first Jewish settlers left the secure walls of Jerusalem to build new Jewish neighborhoods.

But despite this unbearably personal grief, and perhaps in part because of it, Israelis and Jews everywhere feel a sense of unity that keeps us from feeling isolated in sadness.

There is an old poem by Ella Wheeler Wilcox stating that when you laugh the world laughs with you but when you weep you weep alone. That is not the case for Jews, and especially for Israelis. There, and within all Jewish communities who follow traditional mourning practices, no one is ever alone when they are grieving. A whole country grieves with you.

And that is one secret to overcoming the plague of loneliness that is afflicting our world. This podcast-sermon, which I gave this past Shabbat, discusses that plague in a more general context, framed by the Torah portion Kedoshim. But grief is not the only source of isolation and sadness. This sermon briefly discusses some of the causes and possibly remedies, and features an unforgettable experience that happened when I first came to Stamford, in 1987.

SERMON NOTES AND TEXT:

I’ve been reading a lot about loneliness lately.

Back in the pre social media era, a landmark book by Robert Putman called “Bowling Alone” decried the decline of old-time bowling leagues. People were still bowling, he claimed, and a lot of them – but they were bowling alone.

Now new studies show that social media has caused an epidemic of loneliness, especially among young people.

"Unfortunately, what we have learned is that being connected through technology does not necessarily promote feelings of connection.” Said Psychologist Nicole Sigfried to Business Insider, “In fact, most research demonstrates that loneliness increases with increased use of technology, especially social media sites."

The AMA Journal of Ethics adds: “Studies conducted prior to and during the pandemic demonstrate an association between what’s called “internet addiction” and loneliness.”

And a Washington Post headline last December: “For the Lonely, technology offers friendship, at a price.”

And, in case you’re wondering how timely it is, just today, the New York Times ran a front-page story on the topic TODAY!

Under the headline, “Loneliness Shapes Behaviors” it states, “Feeling chronically disconnected from others can affect the brain’s structure and function.” Chronic loneliness, it adds, can lead to cognitive decline.

There are all kinds of reasons to join bowling leagues, or, I should add, to attend houses of worship.

But we didn’t need the AMA or NYT to tell us that. It’s right there at the very beginning of this week’s Torah portion.

Kedoshim means holiness and the portion, which literally falls right in the middle of the Torah, takes center stage in explaining what an ideal society would look like, a holy society. A place where there are no grudges, no hatred, where don’t stand idly by the blood of their neighbor, where provisions are given to the poor. And at the center of it all is the Golden Rule, “Vahavta Rayecha Kamocha,” which, as I’ll talk about more tomorrow, doesn’t just mean your neighbor in your pew, but non-Jews too. Everyone.

The portion’s first two words say it all.

KEDOSHIM T’HYU! – be holy (in plural)

Holiness can happen ONLY where there are other people.

– Rashi points out that the mitzvot found here are all communal - / leave the corner for the poor / don’t gossip / pay workers / don’t put a stumbling block before the blind / LOVE YOUR NEIGHBOR AS YOURSELF

The Kedusha and the Kaddish – two prayers with the same root word of holiness – are among the few prayers that you can only say with a minyan – that’s because they require a response.

It’s a little like the tree falling in the forest. If there isn’t a community to acknowledge God’s holiness, is God really there? Is God’s PRESENCE really felt?

If a person is mourning alone, can God really provide comfort. You need a minyan. Loneliness is not only bad for a person’s mental health, it can be dangerous for society as a whole.

In the final chapter of The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt arrived at the essential condition for totalitarianism: loneliness. “What prepares (people) for totalitarian domination in the non-totalitarian world,” she wrote, “is the fact that loneliness, once a borderline experience usually suffered in certain marginal social conditions like old age, has become an everyday experience of the ever-growing masses of our century.”

Loneliness is the key, then, to the success of fascist uprisings and other populist movements.

In an article in New Statesmen, Lee Siegel writes. “With liberalism under attack from populist movements on the right and left, and stumbling under its own neoliberal and libertarian mutations, you might think there would be a great ferment in the way loneliness is discussed and represented in culture – especially in America. After all, America has invented new forms of loneliness the way Picasso invented new forms of art.” But such is not the case. In order to address the mass pyschosis that has led millions to deny reality and follow a demagogic leader, we have to address their loneliness.

But for Jews it has always been understood that communities and individuals need to be connected to thrive.

You’ve heard of “faith-based communities?” Ours is a community-based faith.

But at the same time we must not be afraid of solitude. We must hear its cry and embrace it. Solitude is a prerequisite for solidarity.

Nachman of Bratzlav and the early Hasidim understood that.

“Grant me the ability to be alone,” he wrote.

“May it be my custom to go outdoors each day among the trees

and grass - among all growing things and there may I be alone,

and enter into prayer, to talk with the One to whom I belong.”

His message is that even when we are alone, we are not really alone. And during times of solitude we can best perceive that.

But while the sacred might be perceived in solitude, holiness is best done in community. Kedoshim Tiyhyu.

Which brings me back to one of my earliest memories here. Christmas Eve: 1987. Just a few months after my arrival, I joined several of us at the local homeless shelter, the old New Covenant House, allowing the Christian volunteers a night off. I must confess that were it not for the tug of my profession, I might well have stayed home. I’m no saint and my body was not sorely needed and it was very cold that night. But I felt I belonged at the shelter. So I went - and did not regret it.

At first, I felt useless. By the time I arrived the food was ready to be served and fifty or so had already come in from the cold and lined up to receive their dinner, cafeteria-style. I managed to make myself useful by dishing out stuffing from an aluminum tin.

As the guests passed by, I would say “Stuffing?” and they’d nod, eyes glued to the floor. There was a lot of despair back then. Multiple crisis, homelessness, AIDS, a stock market collapse leading to more financial hardship. Half a dozen went by, maybe more. Then came this small girl of six - or seven at the most, escorted by a guardian. I couldn’t let her pass the same way, just another faceless encounter. A little girl, who seemed to be without a family on Christmas. At that time there was no separate shelter for families or kids. As she walked past, I dished out some stuffing, and searching for the right thing to say, blurted out, “Merry Christmas.” And what I suddenly witnessed were the two brightest thank-you-Santa eyes I’ve ever seen. There is a line in the finale of the musical version of “Les Miserables,” “To love another person is to see the face of God.” When I think of that girl’s face, suddenly the line took on a whole new meaning for me.

That one moment encapsulated all that makes my job worthwhile. All the meetings, the little petty complaints that sometimes nagged at me, the 3 AM phone calls, it all suddenly became worth it. To ease another person’s loneliness is to ease one’s own. I was able to understand why the word “religion” comes from the Latin, meaning “to bind.” For that girl and I were at that moment bound by religion, both hers and mine.

That little girl’s case was extreme, but each of us in his or her own way sometimes feels the same overwhelming emptiness she must have been feeling. We all at times feel that no one cares. We all feel forgotten. We all are lonely.

Walt Whitman wrote:

I saw in Louisiana a live oak growing.

All alone stood it and the moss hung down from the branches.

Without any companion it grew there uttering leaves of dark green.

And its look -- rude, unbending, lusty, made me think of myself.

But I wondered how it could utter joyous leaves,

Standing there alone without its friends near.

For I knew I could not.

Whitman understood that the oak drew its strength and majesty from within. It needs no other trees in order to utter joyous leaves. But he realized that without other people around him he would not be able to flourish like the oak, for he would want to share that strength with others.

Let us try to be like the oak, drawing strength from within.

Let us be like the poet, sharing that strength with others.

Let us never close ourselves off from others.

Let us strive for holiness COLLECTIVELY, Kedoshim tehyu, always in the plural, but let us never be afraid to be alone.

Share this post